|

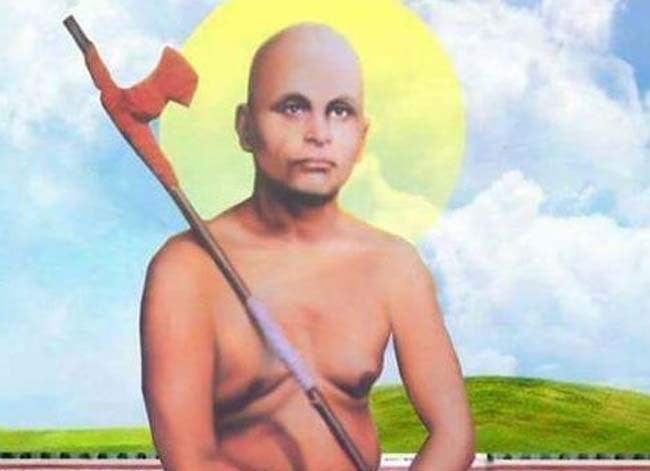

06/02/2019 Who Should Claim Swami Sahajanand Saraswati?

|

The book launch of the English translation of Swami Sahajanand Saraswati’s autobiography The Struggle of My Life (translated and edited by Ramchandra Pradhan, Oxford University Press, 2019) at the Nehru Memorial Museum and Library (NMML), New Delhi on 17 January 2019 is symptomatic of the intellectual politics of the current political regime. The discussion on the book was opened by Shakti Sinha, Director, NMML followed by K. C. Tyagi (Former MP, Rajya Sabha, JD (U)), B. B. Kumar (Chairman, ICSSR), Raghu Thakur (President, Loktantrik Samjawadi Party) and Dr. Jawaid Alam (Historian, Jamia Millia Islamia University); though scheduled to speak, Manoj Sinha, a central ministerand Rambahadur Rai, Chairman, IGNCA, could not make it to the launch. Interestingly, all the panellists spoke in Hindi, and naturally so given the huge Hindi speaking, Uttar-Pradesh-Bihar origin upper-caste (mainly Bhumihar audience) which had filled the seminar room to the brim. Quite curiously, they all lamented the lack of appreciation of Saraswati’s originality as a political thinker owing to his oeuvre being published for so long in the Hindi language alone. The common refrain was that Saraswati’s corpus of work went under-noticed, if not completely ignored and unrecognized, by the left-liberal intelligentsia as the latter was unequivocally English language oriented in both thought and practice. Even when the left-liberal intelligentsia took note of Swami Sahjanand, they reduced him to a mere peasant leader.There are two issues to be taken note of here: first, prior to Ramchandra Pradhan, the historian Walter Hauser (and K. C. Jha) translated and published Saraswati’s major works including his autobiography in English, and second, translating and publishing Saraswati’s autobiography yet again and that too in English was also a genuflection to the same (English language (ideology) oriented) class and its intellectual data base. The panellists, not surprisingly, failed to stay consistent in their own arguments. These factual and finer points aside, what came through strikingly was the concerted intellectual effort to politically appropriate Swami Sahajanand Saraswati, as hurriedly as possible,to expand the historical pantheon of the key intellectual-political figures that the current political dispensation needs so badly. This business of appropriation of the historical legacies of important public figures is being carried out by the present ideological-political regime in three inter-related ways. First, it is trying to widen the wedge, real or perceived, between Jawaharlal Nehru and other Congress leaders. Consequently, the latter is used by the BJP to undermine the Nehruvian legacy which, we all know, is its central goal.By casting Nehru aside, the BJP, with the help of other well-regarded Congress leaders is working towards adding to the ideological legitimacy of its own cultural-nationalist project. Two prominent Congress leaders are cases in point here: one, Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel and two, Netaji Subhash Chandra Bose. The BJP has gone to great lengths to establish Patel as a leader who is neither no less taller than Nehru nor insignificant in the national movement. However, Nehru and the Congress not only failed to give Patel his due but also erased him from the post-independence Indian public imagination. It is this historical wrong that the BJP sought to correct by, among others, installing Patel’s huge statue – the world’s tallest one befittingly called Statue of Unity – in Gujarat. A similar method is adopted in case of Bose whose political differences with Nehru and Congress have been a boon in disguise for the BJP. Here is yet another iconic leader who required rehabilitation, for Bose, argued the BJP, isperhaps the one treated most unjustly by the Congress. The naming of one of the islands of the Andaman and Nicobar archipelago after Bose was BJP’s attempt to recognize the leader’s great contribution, something the Congress always denied him. Patel and Bose, therefore, have been forcefully added to the BJP’s otherwise short list of icons; they are now in the company of the likes of Deen Dayal Upadhyay and Shyamaprasad Mookerjee. Second, there is an attempt by the BJP aligned intellectuals to demonstrate that leaders like Saraswati were not committed to any ideology as such. Many like Saraswatimay have been communists but not like the doctrinaire ones belonging to the established communist parties; leaders like these are projected as believers in freedom of thought and ideas, a trait which is absent in the otherwise intolerant official Left. Saraswati’s differences with the party centric communists is seen by the BJP as a fertile ground to denounce the Left and gradually claim Saraswati as one its own. By deliberately downplaying the explicit ideological inspiration that Saraswati and others like him derived from communism, the BJP is playing down the hold of the communists over protracted grassroots struggles and larger egalitarian politics. The same strategy has been applied to the case of well-known Hindi litterateur and political thinker Rahul Sankrityayan as well. Third, the BJP is bent on drawing maximum attention to the indigenous elements of thinking of leaders like Swami Sahjanand Saraswati. Unlike many communist leaders, Saraswati was introduced to communism through his active leadership of many a grassroots peasant struggles; he started, as social anthropologists would say, with the “field-view” of the peasant condition and in course of time, graduated to the “book-view” of peasant condition. His prolific writings stand testimony to this transition. Having taken to Marx, Lenin and other thinkers advocating a class-based approach to politics, Saraswati found communism to be an appropriate ideological tool to understand and transform the state of the Indian peasantry. Hence, Saraswati’s communism, expectedly, came first from the ground and later fed into what he learnt from the books. Put another way, Saraswati was a product, first and foremost, of the Indian indigenous landscape, an organic leader of the national movement in the Gramscian sense. But to readSaraswati’s indigenous articulations of the politics of his times as evidence of his lack of strong belief in the ideology of communism is politically mischievous and historically misleading. And this is precisely what the BJP is doing, and it was obvious at the NMML book launch. The BJP is using Saraswati’s sensitivity to the indigenous, and his later disagreement with the communists, to point to the illegitimacy of foreign ideologies like communism. Indeed, through Saraswati, the BJP is set to get double ideological benefit: one, the significance of the indigenous and two, the denouncement of communism. The BJP’s project of appropriation has been and continues to be aided, unfortunately and perhaps unintentionally, by the socialists (including the Lohiyaites) of all variety. The peculiar obsession of the Indian socialists like Sampurnanand, Narendra Dev and others with the idea of Indian (indigenous) distinctiveness took away the sheen of their egalitarian socialism. While on the one hand it enabled them to grapple with the reality of caste in a more substantive way, but on the other it led to the total eclipse of the economistic elements of socialist struggles relating to wage workers and tenants. Sadly though, ‘Indian’ socialismhas come to stand for caste-based proportionate political representation and caste-based quota in public employment and education thereby depleting much of its richer historical legacy of a transformative politics. The reasons behind the concerted efforts of the BJP to appropriate a radical thinker like Saraswati is of course clear by now. Saraswati, regrettably, fits the BJP’s scheme of things very well: Saraswati was an Indian monk, a communist but not doctrinaire in the strict sense and finally an upper-caste Bhumihar man whose early activism was around the ritual upliftment of the Bhumihar Brahmins through its caste association. The last indicator is crucial at this point in time. The recent electoral loss suffered by the BJP in the northern-central states put it in panic mode. The fear of losing upper-caste votes in the Hindi heartland in the forthcoming parliamentary elections has pushed it to bring in the legislation of 10% Economically Weaker Sections (EWS) quota for the unreserved category of voters. The NMML book launch too must be seen in this context. As a symbolic gesture, the launch meant paying tribute to one of the stalwarts of the upper-caste Bhumihar community of the eastern Uttar Pradesh and Bihar. Predictably, the discussionhighlighted Saraswati’s Bhumihar credentials and his fight to secure the rights of his caste to perform priestly duties; the fact that the fight actually indicated Saraswati’s challenge to the established caste hierarchy privileging the Brahmans remained underplayed. In any case, the politics of appropriation is certainly not a new game in town. It has always been there. Moreover, it is not that all historical readings are not political acts. But then historical figures and their ideological-political legacies are not about the past but about the present and the future. The established Left is equally guilty of not including in its iconography its own internal dissenters like Saraswati, for instance. Such radical thinkers thus have become vulnerable to misappropriation by those who have an exclusionary and divisive agenda. *Manish Thakur teaches at Indian Insitute of Management Calcutta, Kolkata. Nabanipa Bhattacharjee teaches at the University of Delhi.

|

|